GreenSquareAccord’s failures are costing us all

Towards the end of September 2024, residents across the country received revised service charge calculations from GreenSquareAccord. The message was blunt: the landlord had underestimated service charges, and residents would now be expected to cover the shortfall.

For residents in Oxford, this translated into an additional charge of roughly £250 per month for six months. The timing could hardly have been worse. These increases landed just before Christmas and ran through the winter and into the new year, at the height of a cost-of-living crisis. For many households, this was not an abstract accounting adjustment but a sudden and significant financial shock.

I had already discussed these increases publicly in a video, which I’ve linked here. At the same time, residents began to push back and ask basic questions about how these figures had been calculated and why such large corrections were being imposed retrospectively.

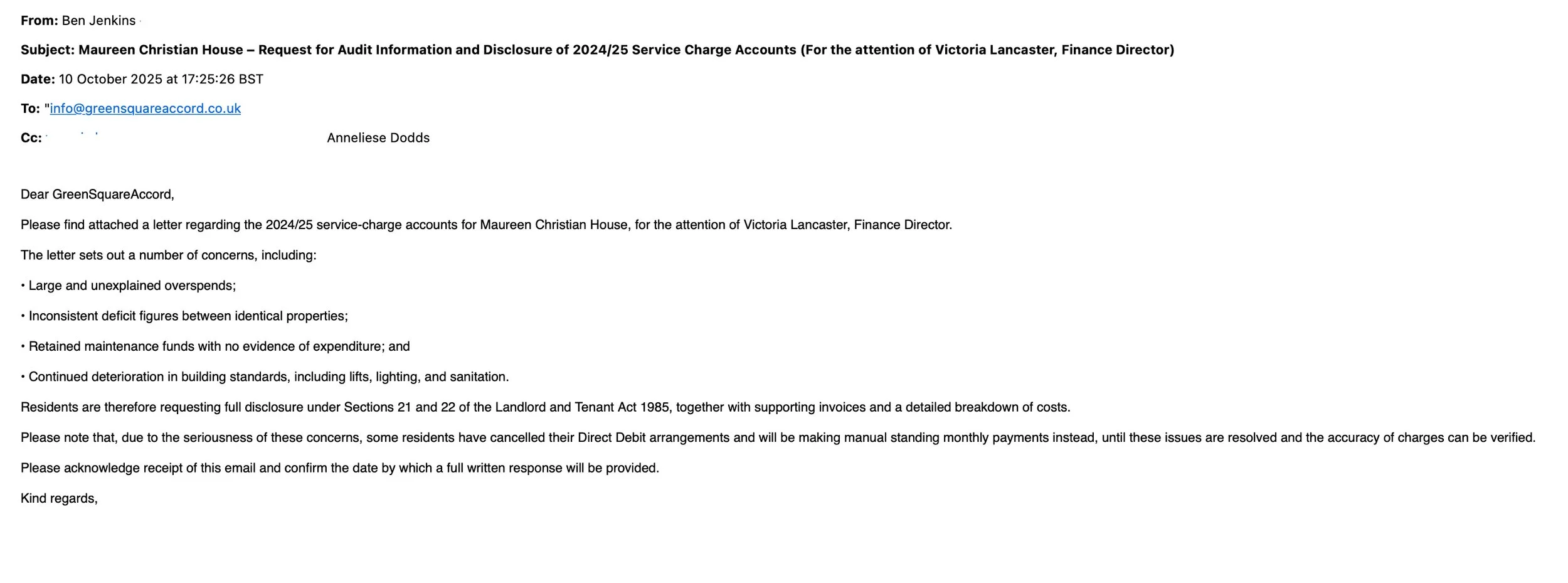

The first red flag was procedural. Our challenge was made under Section 22 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985, which gives landlords 28 days to provide supporting information and evidence. That timeframe was formally acknowledged in writing by GreenSquareAccord’s Finance Director, Victoria Lancaster. Despite this, the deadline came and went. We had to chase repeatedly, and GreenSquareAccord ultimately responded late.

What matters here is not just that the response was late, but that residents were being asked to pay revised and increased charges while the statutory information needed to verify those charges was still outstanding.

When the figures finally arrived, they were still disputed, but something else was immediately clear: there were errors in the original calculations. Errors that GreenSquareAccord itself had to correct.

At first glance, these corrections might appear small or technical. GreenSquareAccord would likely characterise them that way. But it is important to be clear about what actually happened. These were not hypothetical disagreements; they were figures that GreenSquareAccord formally accepted were wrong and had to amend.

Based solely on GreenSquareAccord’s own revised calculations, the admitted error amounted to around 5.2 per cent. In cash terms, that equated to approximately £56.19 per flat. Individually, £56.19 may look insignificant. But service charges are not charged in isolation — they are multiplied across blocks, schemes, councils, and years.

Using a Freedom of Information request to Oxford City Council, I obtained data showing how much public money GreenSquareAccord has received in Housing Benefit alone. From 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022, the figure was £1,144,378. In 2022–23 it rose to over £2.5 million, and by the end of March 2024 it had reached almost £2.7 million.

These figures relate solely to Housing Benefit. Universal Credit is administered by the Department for Work and Pensions and is not included. Discretionary Housing Payments may be made to landlords, but the council confirmed it holds no extractable reports for those payments.

If we take that £2.7 million figure as a reference point and apply the same rule of thumb as the error GreenSquareAccord admitted to in its late Section 22 response, the numbers become more serious. Applying a 5.2 per cent margin across the three-year period produces an indicative figure of approximately £336,000.

This is not presented as a finding or an accusation. It is a simple extrapolation based on GreenSquareAccord’s own admissions and publicly disclosed council payment data. But when councils across the country are struggling to fund basic services, a figure of that scale cannot simply be dismissed.

What is striking is that it falls to residents — people like me and my neighbours — to push back, ask questions, and force corrections from a landlord that otherwise appears to operate with considerable freedom over what it charges.

Many of the figures in this re-estimate also raise serious Section 20 concerns. By backdating and increasing charges, GreenSquareAccord re-exceeded the £250 per-flat threshold that should have triggered formal consultation. In effect, consultation was bypassed. This is not about hindsight or blame. It is about governance, accuracy, and whether residents and public bodies are expected to accept figures first and ask questions later. All of this matters, because it brings us directly to where we are today.

This year’s service charge demands show a clear and substantial increase. They also show deficits being written directly into the accounts and passed on to residents. Taken together with the scale of the figures involved, that alone is enough to justify scrutiny. But scrutiny is not optional. It is built into the law.

Because of the size of the increases, the scale of the deficits, and the concerns raised by the breakdowns provided, residents submitted formal requests under Section 22 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985. These requests were not speculative. They asked for the underlying evidence that supports the charges being levied: invoices, apportionments, and documentation showing how these figures were arrived at.

The reason for asking is simple. Last year, when residents pushed back on similar re-estimated charges, GreenSquareAccord ultimately had to admit that elements of its calculations were wrong. Those admitted errors amounted to around five per cent of the total. GreenSquareAccord chose to draw a line there and told residents that if they wished to challenge further, they should take the matter to the First-tier Tribunal. Against that backdrop, it is entirely reasonable to assume that the figures issued this year should be capable of standing up to scrutiny. If they are accurate, transparent, and properly supported, producing the evidence should not be difficult.

Yet that is not what has happened.

The Section 22 request was submitted on 10 October. It was not substantively acknowledged. Despite this, GreenSquareAccord proceeded to take increased service charge payments while the request for disclosure remained outstanding. Residents were forced to intervene, cancel direct debits, and formally put the landlord on notice that the charges were under investigation.

The request was chased again in early November. It was internally forwarded. Responsibility was passed between teams. And still, no Section 22 response has been provided.

At this point, the silence itself becomes significant.

There are only a limited number of explanations. It may be that it is simply easier to ignore residents who are asking difficult questions. GreenSquareAccord has repeatedly characterised myself and others as “vexatious”, and that label provides a convenient shield: if residents can be framed as unreasonable, their requests can be sidelined without engagement.

It may also be administrative failure. We know from previous correspondence and disclosures that GreenSquareAccord’s internal systems do not always link up cleanly, that information is siloed, and that errors are not always corrected once identified. A Section 22 request that cuts across finance, housing management, and compliance may simply have fallen into that gap.

But there is a more troubling possibility. It may be that these figures cannot be properly backed up at all. That, when tested, they do not withstand scrutiny in the same way last year’s figures did not. Last time, errors were admitted only after sustained pressure. This time, rather than engage, GreenSquareAccord has chosen not to respond at all.

If residents push back on these numbers, the response so far suggests that engagement will not follow. Instead, silence has been met with escalation of enforcement, not transparency.

That silence speaks volumes. And it sets the context for what happened next.

At the point this letter was sent, GreenSquareAccord had still not responded to the Section 22 request. Residents had formally asked for evidence to support disputed service charge figures. That request had been chased. It had been internally forwarded. And it had still not been answered.

Despite this, GreenSquareAccord continued to act as if the charges were settled.

Residents were forced to cancel direct debits because additional sums were being taken while the figures remained under dispute. This was not an attempt to avoid payment. Rent and undisputed charges continued to be paid. The issue was the service charges that were subject to an unresolved statutory request.

It is against that backdrop that this letter was issued.

The letter, dated 3 December 2025, was sent to at least one resident at Maureen Christian House. It states that the resident is “in breach of your lease”, demands payment within seven days, and threatens the issuing of a Notice Seeking Possession — the first step toward repossession of the home. It goes further, explicitly warning that as a shared owner the resident would not be entitled to any proceeds from the sale of their home if possession were granted. This is an extremely serious escalation.

The timing matters. This letter was received just two weeks before Christmas. It was sent to residents living in a mixed community that includes single parents, elderly residents, and people in receipt of Housing Benefit or Universal Credit. Some residents’ housing costs are paid directly or indirectly through public funds. Others are managing on fixed or low incomes. None of that context appears to have been considered.

What is particularly troubling is that this letter was sent while GreenSquareAccord was still in possession of an unanswered Section 22 request! In other words, enforcement action was initiated while residents were still waiting for the evidence needed to verify whether the sums being demanded were correct in the first place.

The letter is signed by Charlie Hall, Home Ownership (Customer Accounts) Officer. However, this is almost certainly not a frontline decision. It is a consequence of senior leadership choices. If GreenSquareAccord’s Finance Director, Victoria Lancaster, its Head of Governance, Sophie Atkinson, and its Chief Executive, Ruth Cooke, choose to ignore a statutory request for information, they cannot then allow enforcement letters threatening possession to be issued as if no dispute exists.

This pattern is familiar. Legitimate questions are not answered. Statutory processes are not respected. Residents are labelled difficult or vexatious. Responsibility for the fallout is pushed downward, with mid-level staff left to put their names to letters that carry life-changing consequences.

Threatening possession while withholding evidence is not neutral administration. It is a pressure tactic. It forces residents to choose between compliance and fear, rather than transparency and accountability. That raises a fundamental question: if GreenSquareAccord is confident in these figures, why has it still not produced the evidence to support them? That question becomes even more important when the consequences of getting it wrong are this severe. Threatening possession while withholding evidence is not neutral administration. It is a pressure tactic. It shifts the balance of power sharply and deliberately, forcing residents to choose between compliance and fear, rather than transparency and accountability.

Threatening possession while a Section 22 request remains outstanding, having been ignored, is not a neutral administrative act. It raises serious legal and ethical questions about how GreenSquareAccord exercises its powers over residents. Section 22 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985 exists for a reason. It gives leaseholders and shared owners the right to see the evidence behind service charges they are being asked to pay. Until that information is provided, the figures remain unverified. They may ultimately prove to be correct, partially correct, or wrong. But without disclosure, residents cannot know.

What makes this situation particularly concerning is that GreenSquareAccord proceeded as if the dispute did not exist at all. Charges were pursued, direct debits were taken, and when residents intervened to stop disputed sums being withdrawn, the response was not engagement or disclosure, but escalation. Issuing a Notice Seeking Possession is one of the most serious steps a landlord can take. It is not a reminder. It is not a nudge. It is the formal beginning of a process that can end in someone losing their home. Using that mechanism while withholding statutory information fundamentally undermines the purpose of Section 22.

Ethically, this approach places residents in an impossible position. Pay first and ask questions later, or assert your legal rights and face enforcement action. That is not a fair balance of power. It is coercive.

The inclusion of language warning shared owners that they would lose any equity if possession were granted sharpens that pressure further. For many residents, their home is their only asset. To introduce that threat while an evidence request is unresolved is deeply troubling, particularly when those residents include people on low incomes, single parents, older residents, and households reliant on Housing Benefit or Universal Credit.

From a governance perspective, this should never have been allowed to happen. Senior leadership cannot plausibly separate the failure to respond to a Section 22 request from the decision to pursue arrears enforcement. These are not independent processes. They are directly connected.

If GreenSquareAccord’s senior team believed the charges were robust, the correct response was to provide the evidence promptly and transparently. If they believed errors might exist, enforcement should have been paused until the position was clear. Instead, residents were met with silence followed by threat.

That is not how a responsible housing provider should operate. It exposes residents to unnecessary distress and exposes the organisation itself to reputational, regulatory, and legal risk.

There is also a wider public interest issue. Where housing costs are paid in part or in full through public funds, councils and government departments rely on landlords to submit accurate, defensible charges. If residents are being threatened into paying disputed sums without disclosure, it raises legitimate questions about oversight and accountability far beyond a single building.

At its core, this is not about one letter or one block. It is about whether statutory safeguards for residents are treated as meaningful obligations, or as obstacles to be worked around. The way GreenSquareAccord has handled this dispute suggests the latter.

And that brings us to the final and unavoidable question: if this is how challenges are handled when residents push back, how many others simply pay because they are too afraid not to? That is the question regulators, councils, and sector bodies should now be asking.

Alongside rising service charges and the aggressive pursuit of disputed deficits, residents have continued to receive a very different set of messages from GreenSquareAccord.

In August 2025, shared owners were written to and encouraged to increase their ownership stake through staircasing. The letter promotes the benefits of buying additional shares, highlights potential reductions in rent, and offers a limited-time financial incentive to proceed quickly. It presents an organisation that is confident, supportive, and keen for residents to invest more money into their homes. Set against the backdrop of what residents are actually experiencing, this messaging feels deeply disconnected from reality.

At the same time as residents are being asked to staircase, GreenSquareAccord has been taking steps to dispose of assets and retreat from projects that have failed financially. The organisation has publicly confirmed that it has been searching for a buyer for LoCal Homes, its offsite housing manufacturing subsidiary, after it became loss-making. Trade press reporting makes clear that this was not a marginal issue, but a significant financial problem that GreenSquareAccord could no longer sustain.

This is not an isolated example. GreenSquareAccord has repeatedly shifted its position on the sale of existing homes. Residents have seen commitments made, withdrawn, and then reintroduced revealed again under different political or financial pressures. Homes fall into disrepair, become increasingly expensive to fix, and are then framed as liabilities rather than responsibilities. But these are not abstract “units” on a balance sheet. They are people’s homes.

Overlaying all of this is the Regulator of Social Housing’s judgement. GreenSquareAccord has been downgraded. Governance and financial viability concerns have been formally recorded. The regulator’s findings are not speculative; they are based on evidence of how the organisation is being run and the risks that flow from that.

Taken together, these strands tell a consistent story. Projects have failed. Assets have underperformed. Costs have escalated. And financial pressure has increased.

It is therefore entirely reasonable to ask where the cost of those failures is landing.

When service charges rise sharply, when large deficits appear year after year, when reserve funds grow without corresponding visible improvements, and when residents are threatened with possession for disputing figures that have not been evidenced, it is fair to question whether residents are being used to absorb the consequences of wider organisational failure.

This is not an accusation made lightly. It is an inference drawn from the available facts. GreenSquareAccord has exited loss-making ventures. It has been criticised by its regulator. It has struggled with the condition of parts of its housing stock. And at the same time, it has increased the financial burden on residents while reducing transparency. If an organisation is under financial strain, there are only so many places the pressure can go. When residents are the least powerful party in the system, they often become the easiest place to apply it.

That brings us to the uncomfortable question that sits beneath all of this: if this is the financial direction of travel, why are residents being asked to pour more money into the same system? Why staircase into an organisation that appears to be firefighting rather than stabilising? Why accept escalating charges on trust alone, when trust has already been eroded by errors, delays, and threats?

If this is a sinking ship, then throwing more money at it won't make it seaworthy, why, as residents, are we being asked to throw good money after bad. Should we have to fund what is looking more and more like a ‘fools folly’ with every passing financial statement

And this is no longer just a resident issue. It is a public money issue. Councils are paying millions in Housing Benefit to the same landlord. If costs arising from mismanagement, failed projects, and regulatory breaches are being quietly redistributed through service charges, then councils have a duty to ask questions too.

The limits of council oversight — and why that matters

What this situation also exposes is the very limited role local councils play once service charges are set in motion.

Councils that administer Housing Benefit do not investigate service charge disputes between landlords and tenants. They are not empowered to demand invoices, scrutinise underlying expenditure, or enforce compliance with Section 22 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985. That statutory right sits with tenants, not public bodies.

When service charges increase, councils apply a high-level “reasonableness” check. This is a comparative exercise, based on previous years’ charges, inflation, and broad comparisons with similar services. It is not a forensic audit. It does not involve examining receipts or verifying whether the sums demanded accurately reflect costs incurred.

Where charges appear unusually high, councils may question landlords and seek explanations. In some cases, errors are identified and charges are amended or removed. In others, explanations are accepted. But this process relies largely on information provided by landlords themselves.

In other words, councils do not independently verify service charges before public money is paid, and they do not intervene when landlords pursue disputed sums from tenants while statutory information remains outstanding. That leaves residents exposed.

If a landlord fails to comply with Section 22, continues to withhold evidence, and simultaneously escalates payment demands, there is no immediate public authority stepping in to stop that behaviour. Tenants are instead told to pursue lengthy complaints routes, often after harm has already been done.

The consequences of that gap are not theoretical. They are being felt now by residents facing pressure, stress, and the threat of eviction over charges that have not been substantiated because the landlord has failed to meet its legal obligations. This is why GreenSquareAccord’s conduct matters so much.

In a system where oversight is limited and reactive, landlords carry a heightened responsibility to act lawfully, proportionately, and with care — especially when dealing with vulnerable households. When that responsibility is ignored, the imbalance of power becomes acute.

Section 22 exists precisely to prevent this situation. It is not an inconvenience to be worked around. It is a safeguard Parliament put in place to protect tenants from being charged blindly and bullied into compliance.

When a landlord refuses to honour that safeguard, and councils lack the power — or willingness — to intervene, residents are left carrying all the risk.

That is not how a fair housing system should work, yet this is the GSA Way.

This pressure on residents sits within a much wider and increasingly visible breakdown in local government finances.

Across the country, councils are effectively going broke. Birmingham is the clearest example. In a city where GreenSquareAccord has a significant number of homes, the council has been unable to resolve a prolonged bin strike, with basic services disrupted as the authority struggles to manage debt, liabilities, and competing statutory pressures. When a council cannot pay its bin workers, it is a sign not of isolated failure but of systemic financial collapse.

I have already explored this in detail, asking what council insolvency really means for residents living in social and affordable housing. That question has only become more pressing. As councils slide further into survival mode, their ability to scrutinise housing costs, challenge providers, or intervene early all but disappears. Oversight becomes limited. Accountability becomes fragmented. Risk is quietly pushed elsewhere.

And it does not vanish — it flows downhill.

From council balance sheets to housing associations. From housing associations to residents. From abstract public debt to personal arrears, threatening letters, and the constant anxiety of not knowing whether your home is secure.

For residents already living on tight margins, there is no buffer. Rising service charges pursued without transparency become unmanageable debt. Delays and failures higher up the system are paid for at the kitchen table.

This is the context in which GreenSquareAccord’s actions must be understood. In a system already under extreme strain, choosing to pursue disputed charges while failing to meet basic legal obligations does not simply enforce debt — it amplifies harm.

If councils are collapsing under the weight of debt, and residents are being pushed toward arrears they cannot afford, the issue is no longer about individual disputes. It is about a system that protects institutions while exposing people.

That is not how a fair housing system should work — yet this is the GSA Way residents and councils are experiencing, and have been for far too long.

Ruth Cooke’s leadership, and the repeated failures of GreenSquareAccord under it, cannot continue to be underwritten by taxpayers and absorbed by residents who are already carrying more than their fair share.

And into 2026…

As this year draws to a close, this issue will not simply disappear. Rising service charges, weak oversight, and the pressure being pushed onto residents are structural problems, not seasonal ones. In the New Year, the focus must shift beyond whether charges are merely “fair” in theory, to whether they are transparent in practice. Residents and councils alike have a shared interest in ensuring that service charges are not only reasonable, but clearly evidenced, lawfully administered, and capable of being independently understood and challenged.

Without transparency, fairness is meaningless. And without accountability, trust cannot exist.

As with all posts on this site, GreenSquareAccord has been offered a right of reply. Consistent with the lack of transparency and accountability outlined above, no response has been received.

That silence speaks for itself. This is the GSA Way.