VEXATIOUS: GreenSquareAccord – Blame the Victim!

Most people think “vexatious” just means someone who complains a lot. It doesn’t.

In legal terms, it is a serious label. It implies bad faith. It suggests someone is acting maliciously, abusively, or deliberately trying to cause harm rather than resolve a genuine issue.

That threshold is high. But at GreenSquareAccord, the word didn’t stay legal. It became cultural, and once it entered the building, it spread.

What the Complaints Were Actually About

Before we even get to the label, let’s be clear about what the complaints were.

They included:

Rising service charges without adequate breakdowns

Delays and failures in providing Section 22 evidence

Repairs and maintenance concerns

Safety issues raised by residents

Ongoing lift issues

Transparency around management decisions

Communication failures

The impact of merger decisions on service delivery

To name but a few.

Many of these issues have persisted for years and continue to do so. These were not abstract complaints. They were documented and evidence-led. They were persistent because the issues persisted. If you have to make hundreds of calls or send hundreds of emails before anyone responds, are you at fault for persisting? Of course you’re not.

But from a PR point of view — where they want to post great stats, highlight that complaints are going down, and show that the number of emails has dropped because service now exceeds expectations — you, as the persistent complainer, become the issue.

Whilst they might not have the funds or the ability to fix a leaking roof or ensure a lift is correctly maintained, they do have the ability to blame the persistence on you. That is something they can manage. And they manage it by labelling you as vexatious.

The Shift From Issue to Individual

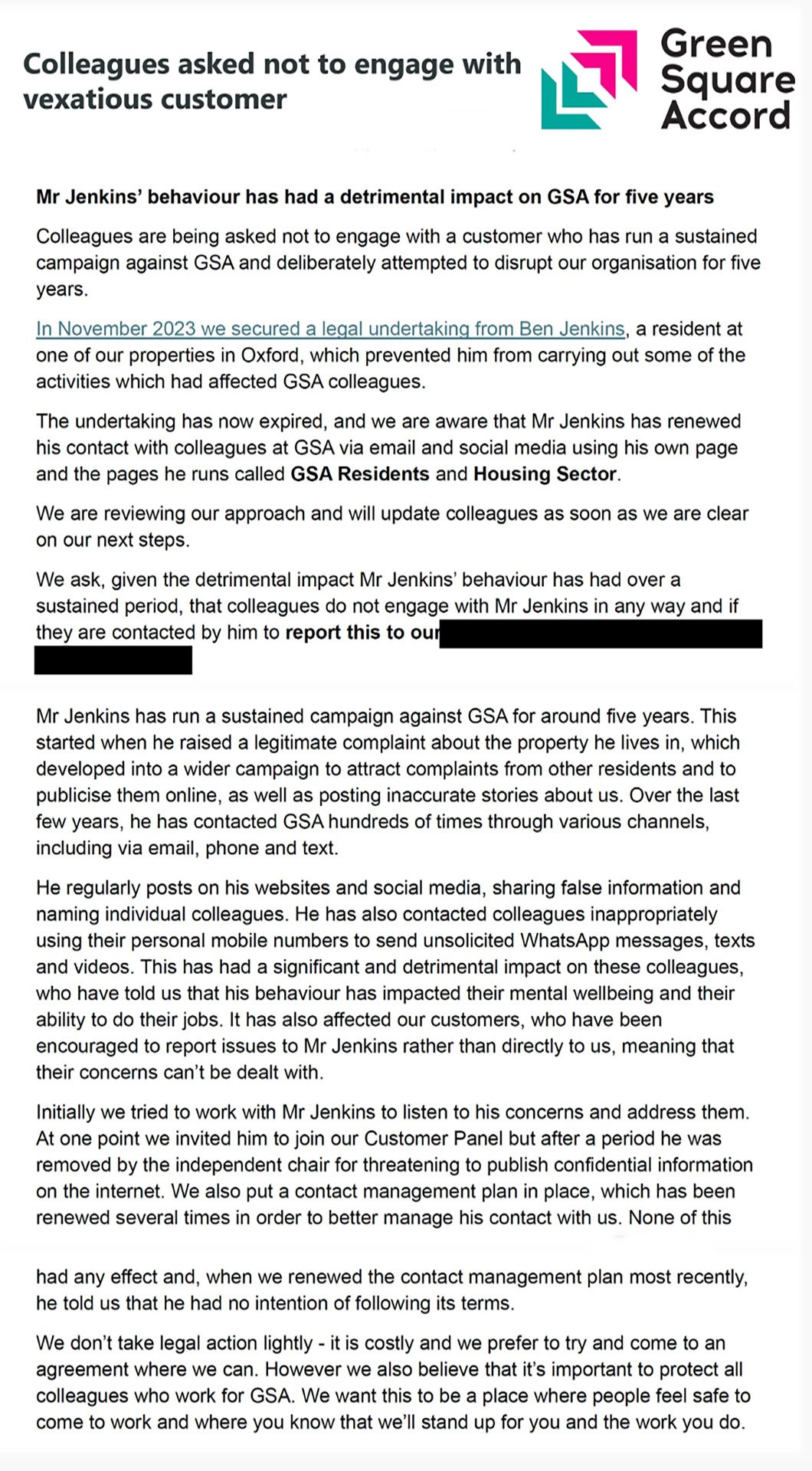

Through a Subject Access Request, internal GreenSquareAccord emails revealed a clear change in tone. The discussion was no longer primarily about the concerns being raised; it was about me.

Contact management plans were put in place to combat my “unacceptable behaviour,” later described on their intranet and within team briefings and internal communications as “vexatious behaviour.” Staff discussions framed ongoing complaints as a management problem. Communication strategies were discussed not in terms of resolution, but containment. Email blocks were put in place to stop me from making senior managers aware of issues that mid-management could not resolve.

The “Hate Group” Narrative

One of the most troubling revelations was that some staff had come to believe I was running a “hate group.” Let that sink in.

A resident website documenting service failures and publishing evidence was internally understood by some staff as something more sinister. That perception didn’t arise in a vacuum. It grew in an environment where internal language framed a resident as problematic rather than engaged.

Once that narrative takes hold, it shapes how staff interpret everything:

A question becomes aggression.

A challenge becomes harassment.

Persistence becomes threat.

The Intranet and Internal Messaging

Internal posts and messaging shared within the organisation reinforced a defensive framing.

Staff were briefed in ways that positioned the situation as reputational risk management rather than a service review. However, ownership of the issue was placed onto me, with claims that it was damaging to the wellbeing of their teams or staff. Staff were advised to report me to the police if they felt threatened by words I published on my resident support site.

There was no internal support structure offered. Instead, they were told to contact the police. I repeat that because it matters. If staff felt threatened by me publishing words on the internet about services not being delivered, there would be no internal mediation or support. The route offered was police escalation.

This was not about staff welfare. It created a pathway to police action against me, which could then be used to justify eviction, frame me as threatening, and potentially leave me with a criminal record if charges were ever brought. That, in turn, would reinforce the narrative they were building — that I was the problem. The person raising the issues was the problem.

Court action. Police action. Legal threats. Communication bans. Outreach into third parties to discredit my name. Dismissing documented evidence as hate speech.

When an organisation’s internal messaging focuses on controlling the narrative rather than correcting failures, it tells you something about priorities.

Residents rarely see intranet posts, but they see the outcomes of them.

Senior Managers and Public Echoes

The internal language didn’t stay internal.

Senior figures used similar framing publicly — including on LinkedIn — where reputational narratives are shaped and reinforced. When leadership subtly or overtly endorses a “vexatious resident” narrative, it signals to staff that the individual is the issue. It also signals to peers in the sector how to interpret events. That matters. Because in housing, reputations travel quickly. And once someone is labelled, that label sticks.

Communication Restrictions and Escalation

Instead of resetting the relationship — as directed by the Housing Ombudsman — GreenSquareAccord moved toward:

– Further contact management measures

– Escalated legal responses

– Framing communication as a staff welfare risk

Again, without evidence of threatening conduct that met the serious legal threshold the word “vexatious” implies.

If you can’t win the argument on facts, you can attempt to win it on tone.

But tone doesn’t fix service charges.

Tone doesn’t repair buildings.

Tone doesn’t resolve safety issues.

Why This Should Concern Every Resident

This isn’t about one person. It’s about a pattern.

When a housing association shifts from:

“We need to fix this” to “We need to manage this resident” the balance of power changes. And once that happens, any resident who becomes persistent, evidence-led, and unwilling to back down risks crossing an invisible line. You move from “engaged” to “difficult.” From “challenging” to “vexatious.” And the focus quietly shifts away from the original issue.

One mistake they made with me — and it was clear from the first threat of legal action by then Customer Service Director Julian Britain — was assuming that escalation would silence me. It didn’t.

By the time legal threats were made, the resident support site already existed. The tactic that may have worked on others — residents afraid of eviction, court action, or arrest, residents who felt they had too much to lose — did not work here.

Instead, the attempt to intimidate amplified the issue. It strengthened the platform. It brought wider scrutiny. It drew attention that might never have existed had the complaints simply been addressed in the first place.

That is the risk of trying to silence someone instead of listening.

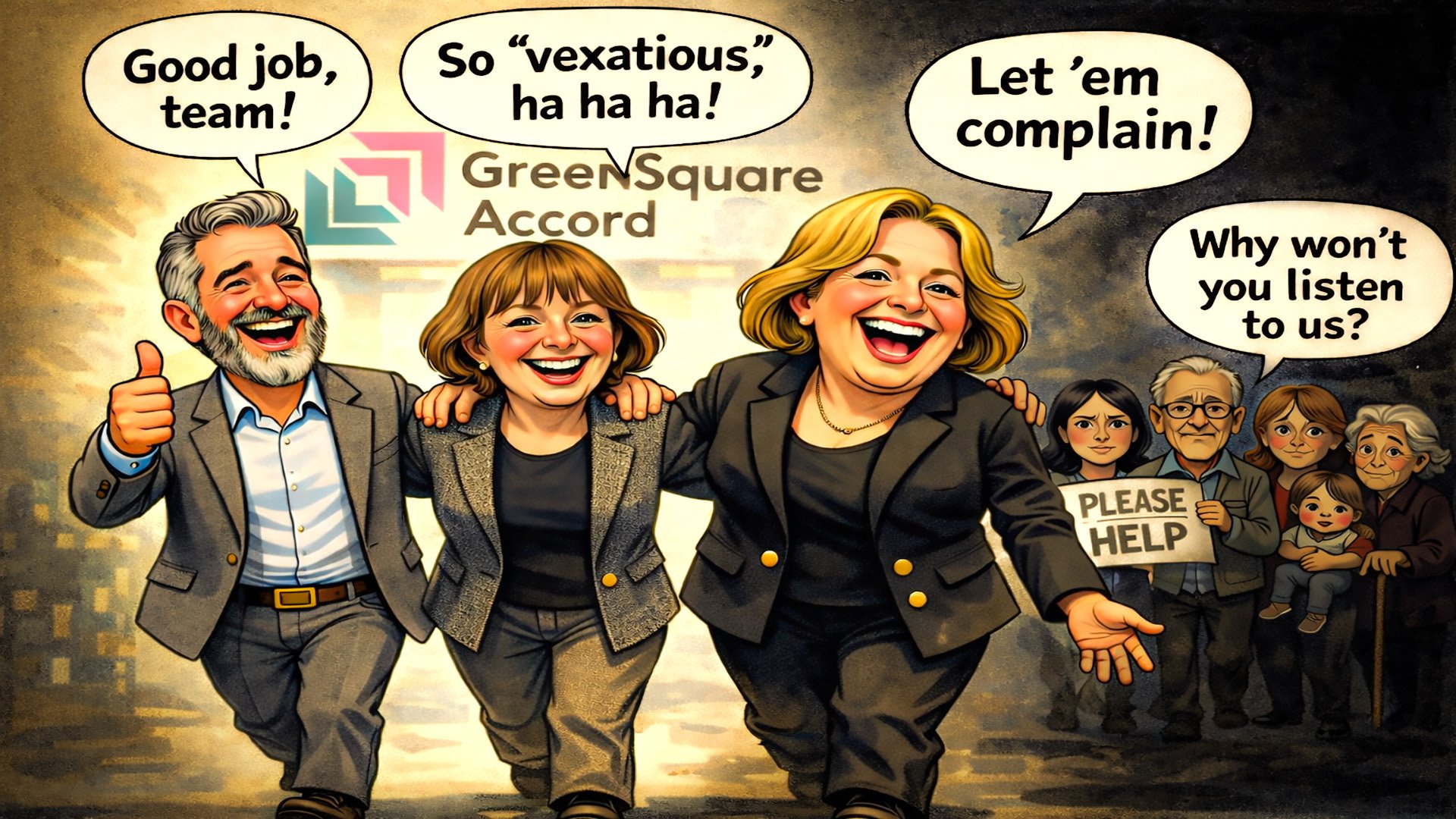

DARVO – The GSA Way!

What happened here follows a pattern commonly described as DARVO — Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender. It is a tactic more often discussed in the context of abusive personal relationships, but the mechanics are the same in institutional settings.

First, the organisation denies the substance of the complaint. Then it attacks the credibility or behaviour of the person raising it. Finally, it reverses the roles, presenting itself as the victim of harassment, aggression, or unreasonable conduct, while the original complainant becomes the offender.

In abusive relationships, DARVO shifts attention away from harmful behaviour and onto the reaction of the person harmed, creating confusion and self-doubt. In organisational disputes, it performs the same function: scrutiny is reframed as misconduct, accountability is reframed as threat, and the power imbalance is reinforced. The original issue — whether safety, service charges, or transparency — quietly disappears behind a narrative about the “problem” resident.

So we must offer our congratulations to GreenSquareAccord. Their practices have placed them in the same category as an abusive partner — a toxic relationship residents find themselves in and are forced to fund. So much for promoting themselves as an organisation with the customer at the heart of everything they do.

The Real Risk

The real risk isn’t that a resident complains too much. The real risk is that legitimate scrutiny is neutralised through language.

If raising concerns about service charges, safety, or governance can result in internal labelling and reputational framing, then every resident should ask - What happens if I speak up next?

Homes are not optional. You cannot simply change landlord. That makes accountability non-negotiable.

Words like “vexatious” should be rare and legally justified. They should never become a cultural defence mechanism. Because once they do, the issue is no longer the complaint.

It’s control.

Further Reading

A more detailed and sector-wide analysis of this issue — including the legal thresholds, regulatory expectations, and broader housing culture — can be read on the Housing Sector website. This loger version examines how the word “vexatious” is defined in law, how regulators expect landlords to use it, and how easily it can slide from a narrowly defined legal term into a cultural label used to neutralise challenge. Because this isn’t just about one organisation. It is about how power responds when scrutiny becomes uncomfortable.

GreenSquareAccord were given the opportunity to respond to this article prior to publication. They chose not to.